In the 2019 election, the Brexit Party stood only in opposition seats and asked its candidates to stand down in Conservative-held seats. Pippa Norris estimates that the impact of this strategy doubled Johnson’s parliamentary majority. So, despite his party being wiped out in this election, Farage’s role has been one of kingmaker in terms of both the predominance of the Brexit agenda and the size of the Conservative majority.

On election night and its aftermath, all the headline attention focused on Boris Johnson’s triumphant 80-seat parliamentary majority, the Conservative party’s largest since 1987. This result is all the more remarkable given years of austerity cuts by successive Tory governments, doubts about Johnson’s flamboyant character, and fratricidal internal party division over Britain’s membership of the EU. The outcome has been attributed to the focused message and disciplined, but ultra-vague repetition of the ‘Get Brexit done’ mantra, and the aggressive targeting of Northern seats with pledges to splash the cash.

Equal attention in the post-mortem focused on the reasons for the collapse in Labour support, especially in their North East Leave-voting, former mill-and-mining heartlands. Labour returned with just 201 seats, their fewest number of MPs since 1935, and their fourth successive general electoral defeat. Much blame has been cast on the unpopularity of Jeremy Corbyn’s leadership, the party’s studious ambiguity on Brexit, as well as their Momentum-led radical-socialist economic agenda, and the party’s unfocused Christmas tree manifesto pledges on welfare spending. Corbyn campaigned on traditional Labour issue like the NHS, but he was not fighting on the Brexit battleground, the most important issue to the electorate.

By contrast, after Nigel Farage’s brief BBC interview with Andrew Neil on election night, there has been relatively little discussion about the Brexit Party. After all, they ended with a paltry 2% of the vote and no MPs. UKIP performed even worse, with 22,817 votes (0.1%). Both parties are seemingly consigned to become a footnote of modern history and the occasional doctoral thesis. Robert Ford, for example, remarked that the Brexit party proved an ‘electoral flop’, with the main effect of their efforts likely to have saved several Labour incumbents by ‘splitting the Leave vote’.

But is this a correct assessment of Farage’s legacy – in particular, what was the broader impact of the Brexit Party on the agenda and results of this general election? Arguably, despite being wiped out electorally, Farage’s role has been one of kingmaker. As Giovanni’s Sartori observed decades ago, minor parties can still serve a critical function through their ‘blackmail’ potential, even if they fail to win seats or ministerial office. The impact of Nigel Farage was both direct – on votes and seats – and indirect – on the policy agenda.

Direct effects on party competition

What matters for the electoral outcome is not simply demand-side factors – long-term shifts in partisan dealignment and generational shifts in cultural values, loosening the salience of the traditional Left-Right economic cleavage and the politics of class, as argued in Cultural Backlash – but also their interaction with supply-side factors. These include strategic decisions by leaders over Downsian party competition, within a broader context of the opportunities for exerting power and influence within the Westminster electoral system.

Thus, one of the key reasons for the outcome, often neglected in the election post-mortems, concerns the impact of strategic party competition, especially whether party leaders decide to informally cooperate with rivals. This is particularly important in the UK, given the high hurdles needed to win office in a majoritarian/plurality electoral system. The Conservative share of the vote under Johnson, after all, went up only 1.4% across the country, almost unchanged from May’s 2017 result. Despite this, the Tories gained 47 seats and the Johnson government enjoys a comfortable 80-seat parliamentary majority, freed from May’s shackles of a government depending upon an informal agreement with the DUP. The outcome should not be attributed necessarily to the supposed brilliance of the Conservative campaign and their leader, the weakness of their opposition, or the disparities of the winner’s bonus in the UK’s First-Past-the-Post electoral system, as other argue, but rather, at least in part, to the spoiler role of the Brexit party combined with divisions over strategy and tactics among opposition parties within the Remain camp, which prevented their effective cooperation. The result reflected the old adage: united they stand, divided they fall. While Farage formed a Leave phalanx with the Tories, the Remain troops scattered their forces across the battlefield.

Figure 1 illustrates how UKIP, and then the successor Brexit Party, both experienced roller-coaster rides in successive local, European, and general elections. UKIP ran 378 candidates in the June 2017 general election – but won just half a million votes (1.8%), with no seats. Despite this wipe-out, the major parties, especially the Conservatives, were rocked by the initial electoral success of the Brexit Party, which won the largest share of the UK national vote and seats in the May 2019 party-list European Parliamentary elections, just four months after founding. Most strikingly, the party swept up almost half of the over-65s. The opinion polls registered around 23% support for the Brexit party at their peak a few weeks later, in mid-June 2019, when they were tied or even a point or two ahead of the two major parties.

Given this result, when the 2019 campaign kicked off, the Brexit Party’s challenge to politics as usual appeared formidable. In early November 2019, as the general election campaign started, the Brexit party initially announced that it would contest all 632 British seats and speculated publicly about a ‘Leave alliance’ with the Tories. But the Conservatives quickly rejected any sort of electoral pact, treating their rival upstarts strategically like a pariah. In response, on 11 November 2019 Farage climbed down and declared that the Brexit party would withdraw in 317 seats won by Conservatives in 2017, to avoid splitting the Leave vote. This, combined with subsequent Brexit candidate defections, triggered a collapse in their popular support. Their share of voting support subsided in the opinion polls from an average of 10% at the start of the campaign to just 3% at the end, as supporters drifted back to the Tories. Farage was still included in media coverage and the larger TV leadership debates, campaigning for a ‘clean-break’ Brexit and political reform, but the Brexit party saw a substantial collapse in their total amount of media coverage during the final weeks of the campaign. Election night saw that Brexit had won just 2% of the vote (642,323), with no seats, while the rump UKIP part got a miserable 22,817 votes (0.1%).

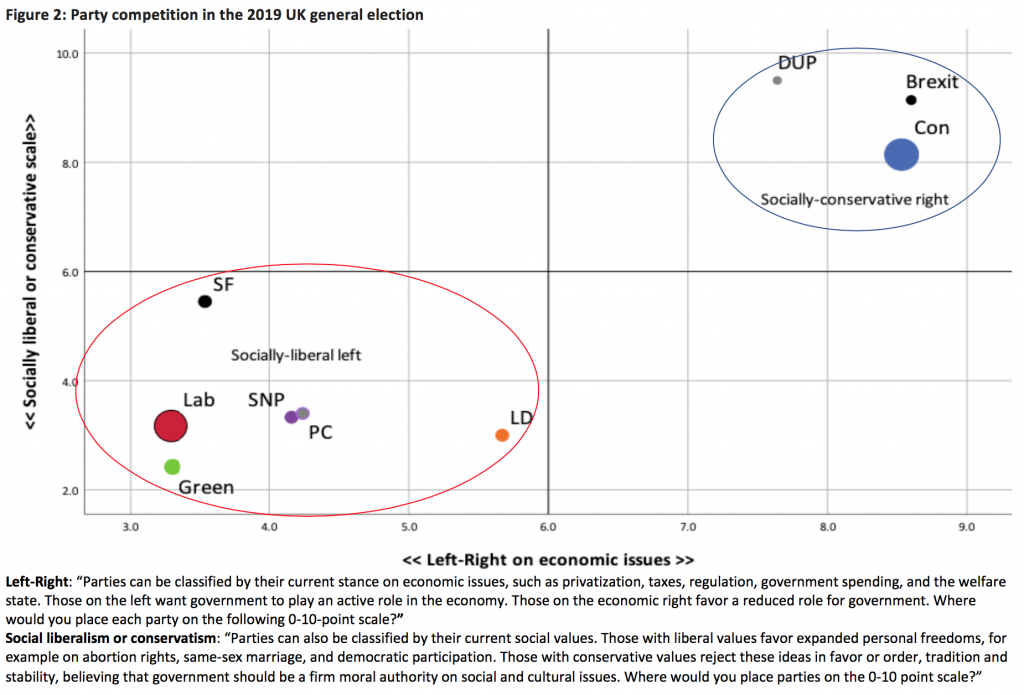

Therefore, Nigel Farage decided to play the long game by competing strategically in the election only in opposition seats, asking Brexit candidates to stand down in Conservative-held seats. This served two goals: as a brand-new party, for expedient reasons, Brexit’s financial and organizational resources were over-stretched. Moreover, the stated aim of this strategy was to present a united front which avoided splitting the Leave vote. This strategy had two consequences: the Brexit Party had opportunities to snatch Leave ballots in Labour-held seats, without simultaneously damaging the electoral prospects for incumbent Conservative MPs. At the same time, the Remain vote remained divided because Corbyn stubbornly ruled out any informal pact and various efforts to organize tactical voting. As Figure 2 illustrates, the Conservatives were flanked by the Brexit Party, but otherwise enjoyed ‘clear blue water’ to shovel up Leave votes on the socially-conservative and nationalist right. By contrast, the socially-liberal left parties were all clustered closely together, able to exchange votes with each other but thereby dividing the spoils and failing to gain seats.

Labour’s strategy continued to reflect leadership hubris and outmoded majoritarian Westminster norms. This proved fatal in the context of fragmented party competition which penalized their chances of consolidating Remain support and gaining seats. In total in Britain, excluding Northern Ireland, the Remain/pro Referendum parties got 16.2 million votes (52.3%), 1.5 million more than the 14.6 million votes cast for the Leave parties (47.4%). The balance of voting support was remarkably close to that estimated in the long series of YouGov polls since late 2017 concerning right track/wrong track levels of support for Leave or Remain options in the general electorate. The outcome of the general election therefore reflects, in part, the disastrous failure of opposition party strategy and leadership to come together in an informal Remain Alliance electoral pact in a First-Past-the-Post system, not simply a triumph of the Johnson campaign, or a failure of the appeal of Corbyn’s personal character, problems of press bias, internal rows over anti-semitism, or Labour’s manifesto policies.

The impact of party strategies

Does the scale of their electoral support mean that we should write off the Brexit party as irrelevant to the outcome – or that Farage failed in his grand project? On the contrary, Farage’s strategic decision to compete in Labour seats, but not in Conservative seats, was arguably decisive for the eventual outcome.

Analysis of constituency results in the 2017 and 2019 general elections shows that in seats where Brexit party candidates stood, the change in the share of the UKIP/Brexit vote was more strongly correlated with the fall in the Labour share of the vote than in the Conservative or Liberal Democrat share. This relationship continued as significant, albeit weaker, even after models controlled for the social composition of constituencies. In seats with a Brexit candidate, the Labour vote fell on average by -8.6%, compared with -7.3% elsewhere. There was also a modest impact with Brexit taking some support from the Tories: in seats with a Brexit candidate, the Conservative vote went up 1.7% compared with 2.5% elsewhere. But my estimates suggest that the share of the Brexit vote was large enough to allow the Conservatives to slip in the back door and make up to 20 seat gains in former Labour areas, thereby doubling Johnson’s eventual parliamentary majority (see Figure 3).

The Conservative party would have won a smaller parliamentary majority without the Brexit party alliance. Farage’s party thereby served as a spoiler, allowing the Conservatives to seize many Labour seats in the North and Midlands which had never changed hands for generations. This bonanza is all the more remarkable given a rise of only 1.4% in the Conservatives’ nation-wide share of the UK vote since 2017. Meanwhile, by contrast, Remain voters on the liberal left scattered support among the Liberal Democrats, the Greens, the SNP and Plaid Cymru, as well as the more ambivalent Labour party.

Indirect effects on the issue agenda

The entrance of UKIP and then the Brexit Party also shaped British politics in an even more profound way indirectly, by mobilizing authoritarian-populist forces and thereby polarizing the country and the policy agenda around Brexit. Mainstream parties on the center-right and center-left can respond to new rivals by strategic attempts at either exclusion (treating their new rivals as pariahs) or else inclusion (by parroting their competitor’s rhetoric and issues positions). Ever since Anthony Downs, the consequences of these strategies have been widely debated in terms of both their electoral effects and their impact on the policy agenda. Farage has obviously failed at gaining office at Westminster – but he has had a profound effect on the policy agenda by forcing other UK parties adapt their policy position towards Europe.

Cases vary, but in many countries, new authoritarian-populist parties have become accepted as legitimate and democratic partners with a seat at the table, thereby directly influencing the issue agenda in parliament and the composition of coalition governments. Elsewhere, however, exclusion from entry to governing coalitions is often common. In Germany, for example, the Christian Democratic Union party refused to collude with the far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD), despite their becoming the third largest party in the Bundestag in 2017. In extreme cases, some authoritarian-populist parties have been banned by law, for example the racist Flemish Vlaams Blok, or otherwise legally restricted from funding or ballot access.

Even where treated as ‘pariahs’, however, minor rivals can still impact the policy agenda indirectly, by forcing the mainstream parties to adjust their stances in response to new concerns, in this case by parroting issues of nationalism and immigration. Johnson’s unprincipled ambitions, and the machinations of the ERG, made the Conservative Party ripe for a hostile take-over by populist forces. In this regard, both major parties have absorbed the cancer of Euroscepticism, mobilized by Farage and the ERG Conservatives, and injected this into the mainstream of the body politics.

In conclusion, the role of the Brexit Party should therefore go down in the history books as one which proved an electoral failure at Westminster, losing the general election battle. But in the long-term, Farage played a decisive indirect role by boosting the size of the Conservatives’ electoral victory, fueling the politics of Brexit, and thus influencing the UK’s withdrawal from EU membership, strengthening the polarization of UK party competition around cultural cleavages dividing nationalists and cosmopolitans, and even potentially heightening existential threats to the future of the United Kingdom as an independent nation-state.

Comments

Post a Comment